By Natasha Wadlington, PhD.

By Natasha Wadlington, PhD.

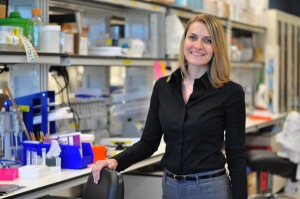

Dr. Virginie Buggia-Prévot is a research scientist at the Institute for Applied Cancer Science at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. She serves as head of neuroscience target discovery and validation at the Neurodegeneration Consortium, a collaboration of MD Anderson, Baylor College of Medicine and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Her role is to act as a liaison between consortium members at MD Anderson and top scientists in the field at MIT and Baylor College of Medicine to find new targets for therapies to stop, slow or reverse Alzheimer’s disease. Her work involves interacting with many of the researchers and postdocs as well as keep up with the changing trends in literature. Virginie finds the experience both enriching and fun.

To arrive at her current position in Houston, Texas, Virginie faced many trials and tribulations. Through perseverance and a great support network, she gained many experiences, accumulated great wisdom and succeeded at finding a career about which she is passionate.

Virginie was born in Grenoble, France. In France, she discovered her love for the sciences and as an undergraduate, working in a lab that focused on Parkinson’s disease. Continuing her focus on neurodegenerative diseases, she completed her Ph.D. at Le Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Nice Sophia-Antipolis, France. There she studied amyloid-beta and found a novel pathway in which it associated with neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. It was at this point Virginie decided to take a chance, leave France and pursue Alzheimer’s disease as a postdoc at the University of Chicago. While transitioning from France to the United States was a challenge, she found that the transition from postdoc to her current position more demanding.

At this point of her life, Virginie knew she had a crucial decision to make.

“At the same time you have to try to find opportunities,” she says.

As a postdoc, Virginie published eight articles in peer-reviewed journals, including work on the transport of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated protein BACE1, obtained $180,000 in grant funding for her research and provided the critical data to help fund a project with collaborators at Northwestern University for $400,000. However, obtaining data and becoming published were not the only keys to her success. She had to learn how to effectively network.

Virginie has learned that postdocs are not always aware of how to network efficiently, with many experiencing “failures and bad experiences.” To combat this issue, Virginie openly sought out sources to network and communicate. She became the co-chair for the seminar and social media committees at the University of Chicago’s Biological Science Division Postdoctoral Association. There were plenty of opportunities to interact with people within the university. She also enjoyed communicating outside the university through social media channels such as Twitter. Aside from gaining access to a community of academics and biotech groups outside of the University of Chicago, she also received followers from peer-reviewed journals and foundations.

“It’s always nice to be able to do something and also to promote the foundations,” says Virginie.

Meeting some of those followers in person was a great way to connect with others personally and professionally. So many postdocs do great work but their exposure may be limited, she says.

“It’s essential to have a good LinkedIn page and to promote your work. Everybody Googles you now,” says Virginie.

She fully used these tools and, as a result of the contacts she gained, successfully transitioned from postdoc to her position at MD Anderson.

Life is not meant to be all work and no play. MD Anderson encourages its employees to maintain a work-life balance. For Virginie, that notion can be a little difficult at times.

“I have a very hard time turning off my brain at night,” she says. “I’m the type of person who will wake up in the middle of the night and draw schematics and write down experiments.”

She has a true passion for science and recognizes that when you love what you do, it can be hard to walk away. Luckily for Virginie, she has found that balance with her husband, a non-scientist. They both value the arts and enjoy visiting museums and traveling in their spare time. She attributes her love for all things culinary to her French roots and takes joy in cooking at home. Virginie has found that great balance between working in an environment that she loves and living her life to the fullest extent.

For people trying to find their way through STEM careers, she offers some wise advice.

“If you are passionate about something, it will be transparent and people will definitely give you opportunities,” says Virginie. “Find people who inspire you and surround yourself with people who believe in you. Share your passions with the world and your friends because you never know where you are going to find your next opportunity. By verbalizing the things you like, the more it would be clear in your head what you are looking for.”

Virginie’s perseverance through adversity and challenges is inspiring to women in STEM everywhere.